RIP CBM Review?

The Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (“AIA”) created three new procedures to be presided over by the newly created Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”). Two of these procedures, post grant review (“PGR”) and inter partes review (“IPR”), are permanent while the third, covered business method review (“CBM”), was intended to be temporary. The CBM program expired on September 16, 2020.

A comparison of these three procedures highlights the differences between them. For example, a PGR petition can only be filed within the first nine months after grant of the patent. An IPR petition can be filed against a patent at any time prior to one year after service of a complaint alleging patent infringement by the IPR Petitioner. In contrast, the ability to file a CBM petition is explicitly triggered by an infringement suit:. “A petitioner may not file . . . a petition . . . unless the petitioner, the petitioner’s real party-in-interest, or privy of the petitioner has been sued for infringement of the patent or has been charged with infringement under that patent.”[1] There is no time bar for filing a CBM petition like there is with IPR and PGR petitions. Additionally, while the validity of a patent can only be challenged on the grounds of novelty and non-obviousness (§§ 102 and 103) in an IPR petition, PGR and CBM petitions can also challenge the validity of a patent on the grounds of patent-eligible subject matter and indefiniteness (§§ 101 and 112).

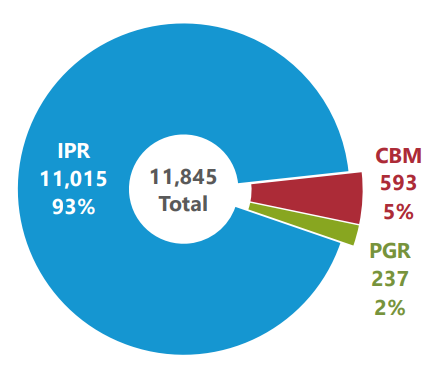

As of July 2020 (the most recent data available from the USPTO at the time the writing of this article), 593 CBM petitions have been filed, which accounts for just 5% of all petitions filed with the PTAB.

Petitions by Trial Type (September 16, 2016 to July 31, 2020)[2]

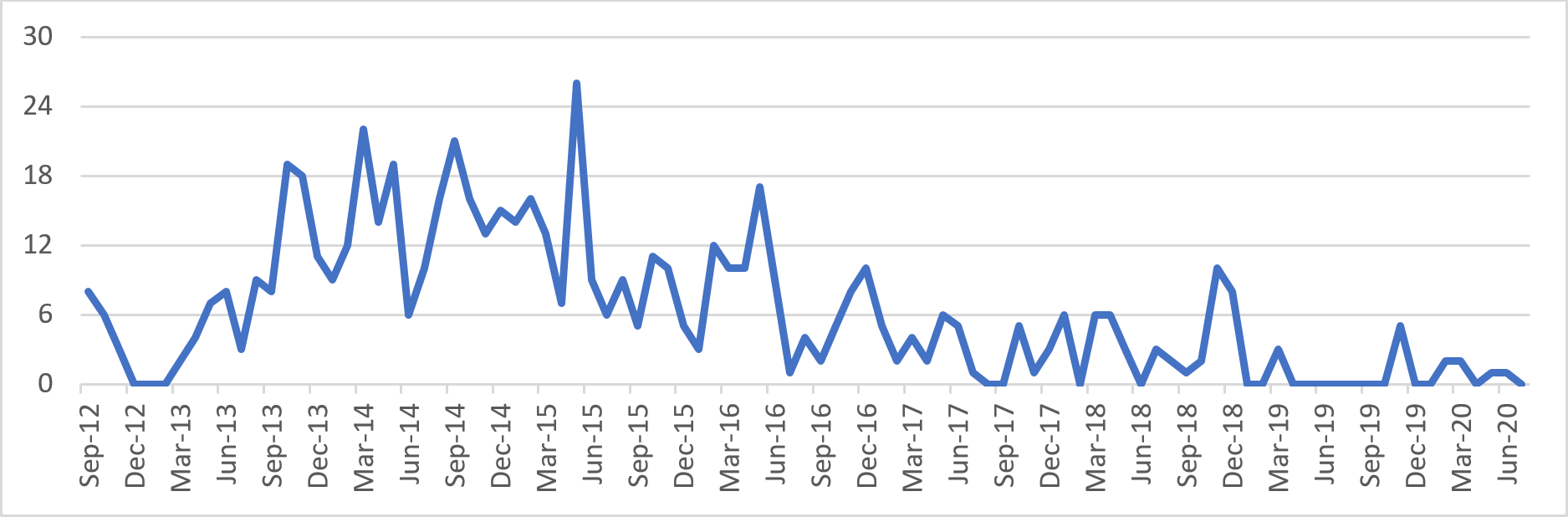

The number of CBM petitions filed saw its peak in between September 2013 and May 2015, after which the rate of new CBM petitions declined. Only about a dozen CBM petitions were filed in 2020.

CBM Petitions Filed by Month (September 2012 through July 2020)[3],[4]

Of the CBM petitions that reached trial, the PTAB ruled that at least one claim was unpatentable in 96% of cases.[5] This result is not surprising, however, based on the standard under which CBM trials were instituted – “more likely than not” that at least one claim is unpatentable.[6] This is a higher standard than the “reasonable likelihood of success” standard applied to IPRs. According to former Chief Judge James Donald Smith, “the reasonable likelihood standard allows for the exercise of discretion but encompasses a 50/50 chance, whereas the ‘more likely than not’ standard requires greater than a 50% chance of prevailing.”[7] Looking at all CBM proceedings, not just those that reached trial, the PTAB found at least one claim unpatentable in 35% of cases.[8]

But only certain types of patents were eligible under the CBM program. The original scope of patent eligible for the CBM program included patents that claimed “a method or corresponding apparatus for performing data processing or other operations used in the practice, administration, or management of a financial product or service, except that the term does not include patents for technological inventions.”[9] Thus, the number of patents potentially covered by the CBM program was very limited. Several court decisions influenced the number of eligible patents. In Cuozzo Speed Technologies, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the PTAB’s use of the broadest reasonable construction standard to define claim language in all post-grant proceedings.[10] This decision increased the number of eligible patents by allowing petitioners to broadly interpret claims to be related to methods related to financial activities. In 2016, The Federal Circuit in Unwired Planet reduced the number of patents eligible for the CBM program by ruling that the USPTO’s test of whether the claimed activity was “incidental” or “complementary” to financial activities was too broad.[11] The Federal Circuit thus limited the CBM program to patents claiming non-technological methods involved in the administration, management, or practice of a financial product or service. The Federal Circuit further clarified in 2017’s Secure Axcess that to be eligible for the CBM program, a patent must specifically have a claim that contains an element of financial activity.[12]

After 2015, the number of new CBM petitions declined. This might be due to the worst patents having been targeted early in the life of the CBM program, leaving only the higher quality patents. The decline may also be due to Alice and its progeny of cases related to patent eligible subject matter. Under the Alice test, the subject matter of many CBM patents would likely not be eligible, but rather directed to an abstract idea. CBM patent owners may have been worried that asserting their patent rights would risk the invalidation of their patents under Alice. Fewer patent owners would have been willing to take this risk and, since an infringement charge is a prerequisite of filing a CBM petition, fewer petitions were filed.

The CBM program was created with special rules as a response to the Federal Circuit’s 1998 decision in State Street v. Signature Financial, in which the Court broadened the scope of eligible subject matter for business method patents. There was concern among stakeholders that many business method patents granted after State Street were overly broad and therefore invalid. Congress therefore created the CBM program as a means to reevaluate the validity of such patents.

The CBM program decreased the value of business method patents for assertion in litigation, as they could be challenged under the CBM program. It served its purpose of reducing costly litigation of business method patents, as do IPRs and PGRs. During the early years of the program, many reports estimated that motions to stay were granted in up to 70% of district court cases where a parallel CBM review proceeding was filed, though actual rates tended to vary by jurisdiction. There was value in parties having the ability to challenge a patent on all four statutory grounds (patent eligibility, novelty, non-obviousness, and indefiniteness) at any time during the life of the patent. (As mentioned above, while all four grounds are available in a PGR, the petition cannot be filed later than 9 months after issuance of the patent.) It could even be said that the looming threat of a CBM challenge was good for overall innovation in the financial technology space by eliminating overly broad patents and causing inventors to focus their inventions on particular areas of financial technology.

The CBM program’s purpose of invalidating overly broad business method patents has largely been served. While the program may no longer be necessary, as the subject matter of most CBM patents would not be patent-eligible by the current standards, it provided a useful and convenient venue in which to challenge those patents without burdening the district courts, as well as an impetus for greater innovation in financial technology. While some may be glad to see the CBM program go, leaving behind a stronger and more focused area of technology, others still feel the program is still necessary. Parties such as the Credit Union National Association, the American Bankers Association, the Electronic Transactions Association, and the National Retail Federation, among other, urged Congress to extend the program by one year, and warned that both practicing patent owners and trolls alike are simply waiting until the expiration of the program to assert their business method patents.[13] On June 17, 2020, a number of executives of financial companies and associations wrote a letter to Senators Tillis and Coons, who sit on the Senate Judiciary Committee, arguing that, rather than being subject to an expiration date, the CBM program “should expire of disinterest, if not to eliminate a proceeding of questionable use, of illegitimate vintage, and of unjust intent.”[14]

It remains to be seen of Congress will heed the calls of those who would see the program continue and reinstate it. For now, though, the CBM program is over. May it rest in peace.

By Jason S. Ingerman

[1] 37 CFR § 42.302(a)

[2] https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/trial_statistics_20200731.pdf

[3] https://www.uspto.gov/patents-application-process/patent-trial-and-appeal-board/statistics

[4] GAO-18-320 https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/690595.pdf

[5] Id.

[6] 35 U.S.C. § 324(a)

[7] Message from Chief Judge James Donald Smith, Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences: USPTO Discusses Key Aspects of New Administrative Patent Trials, https://www.uspto.gov/patent/laws-and-regulations/america-invents-act-aia/message-chief-judge-james-donald-smith-board

[8] GAO 18-320 at 23-24.

[9] AIA § 18(d)(1)

[10] Cuozzo Speed Technologies, LLC v. Lee, 136 S.Ct. 2131, 2136 (2016).

[11] Unwired Planet, LLC v. Google Inc., 841 F.3d. 1376, 1382 (Fed.Cir. 2016).

[12] Secure Axcess, LLC v. PNC Bank Nat’l Assoc., 848 F.3d. 1370, 1381 (Fed.Cir. 2017).

[13] See, e.g., https://www.ipwatchdog.com/2020/09/03/special-interest-group-implores-congress-extend-cbm-program/id=124863/

[14] Letter to Sen. Thom Tillis and Sen. Chris Coons, https://www.ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Ltr-CBM-patent-review-final.pdf