Economics of Diversity

I. Introduction

Diversity and inclusion are topics of increasing corporate and media scrutiny. As this paper explains, hard evidence supports positive economic impact of a diverse workforce within a company or any organization, including increased revenue and market share, and reduced turnover and legal costs. A clear business case for a diverse workforce and investment in diversity initiatives is supported by this paper. In particular, this paper focuses on the economics of diversity within the legal industry.

II. Impact of Workforce Diversity on Revenue

(a) Studies Show Increased Employee Diversity Is Correlated with Higher Revenues

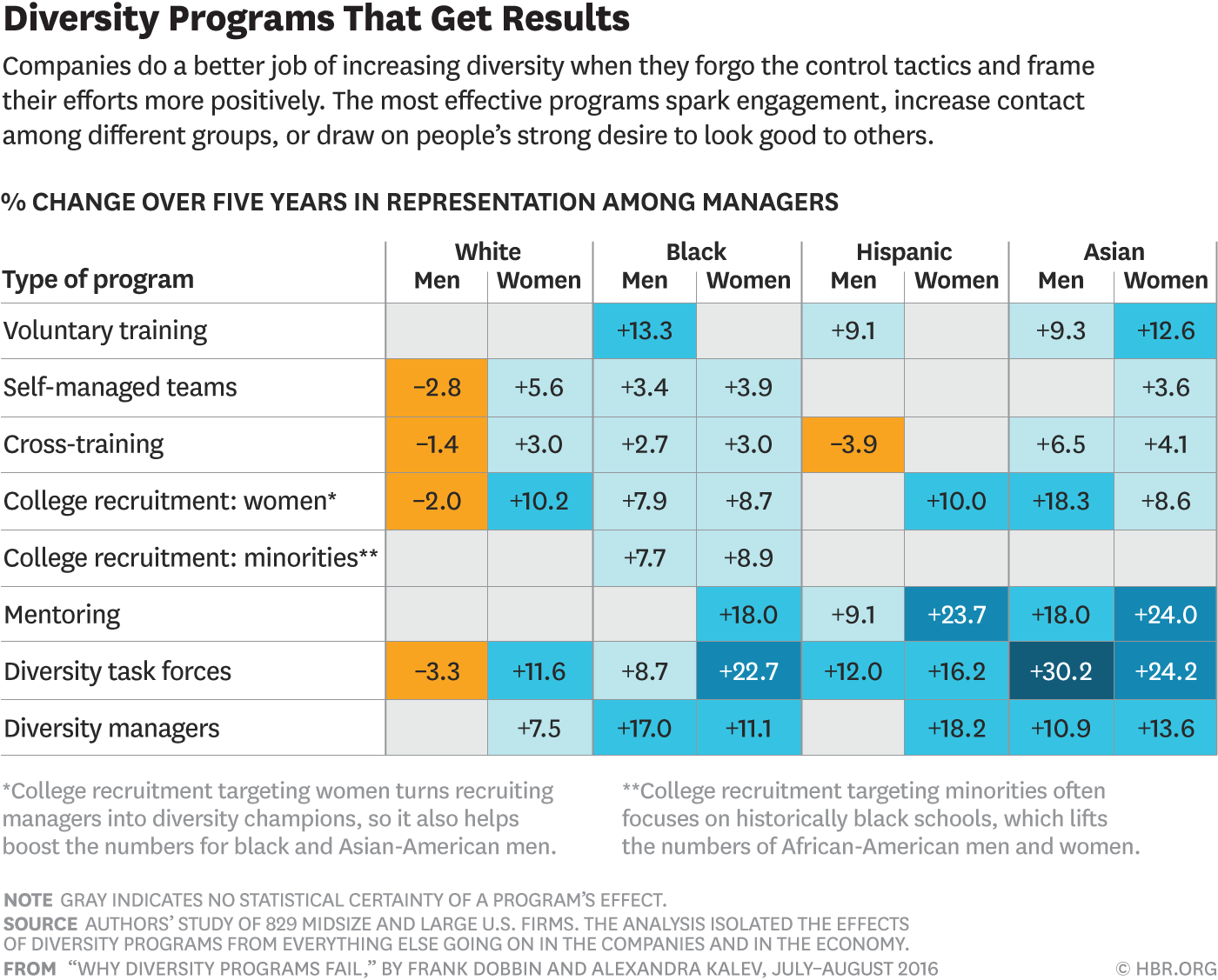

Research shows diversity is linked to increased sales and revenue in organizations. A 2009 study led by Cedric Herring is one of the first empirical examinations of the impact of diversity on business performance.[2] The study found higher levels of workforce diversity are correlated with higher sales revenue.[3] As a workforce’s racial diversity increases, sales revenues increase.[4] As shown in the table below, the mean revenues of a business with low levels of racial diversity are $52.3 million, compared with $323.9 million for medium levels and $808.9 million for businesses with high levels of diversity.[5] That is, the mean revenue of a racially‑diverse business has over fifteen times the revenue of a business with lower levels of diversity.

The study also found that as a workforce’s gender diversity increases, sales revenues increase.[6] As shown in the table below, the mean revenues of a business with low levels of gender diversity are $45.2 million, compared with $302.9 million for medium levels and $639.7 million for businesses with high levels of diversity.[7] That is, a more gender‑diverse business posts revenues over fourteen times greater compared to a business with lower levels of diversity.

Table 1: Means and Percentage Distributions for Business Outcomes of Establishments by Levels of Racial Diversity and Gender Diversity

After isolating other potentially causative variables, Herring found that racial and gender diversity are important predictors of sales revenue. For instance, a one unit increase in racial diversity increased sales revenues by 9% while a one unit increase in gender diversity correlated to a 3% increase in sales revenue.[8] In particular, racial diversity is a more powerful predictor of sales revenue and customer numbers than company size and company age.[9]

A 2018 McKinsey & Company study update shows Herring’s finding that the positive relationship between diversity and financial performance stands the test of time.[10] The study found a statistically significant correlation between workplace diversity and profitability.[11] More specifically, the profitability of companies in the top quartile for gender or racial and ethnic diversity are more likely to outperform the average profitability compared to companies in the bottom quartile.[12]

The McKinsey study considered more specific nuances of gender and ethnic diversity compared with Herring’s study. It analyzed gender and ethnic diversity data at the executive and board levels.[13] The study found diversity at the top of an organization is just as important as diversity overall. For example, a diverse group of decision makers is associated with an increase in a company’s likelihood of profitability. It also used a global data set, which showed that diversity increases profitability across multiple geographical locations and cultural norms.[14]

The study was broken up into findings on gender and ethnic diversity. For gender, more gender‑balanced executive teams yielded enhanced profitability across all geographies.[15] Companies in the top quartile for gender diversity at the executive level are 21% more likely to have above‑average profitability compared with the bottom quartile.[16]

Ethnic diversity resulted in an even higher likelihood of profitability. Companies in the top quartile of ethnically diverse boards were 33% more likely to outperform the national industry median in profitability compared with the bottom quartile.[17] This was true not only in terms of absolute representation, but also in terms of the range of ethnicities represented.[18] Ethnic diversity at the board level was also associated with a 43% likelihood of higher profits, worldwide.[19]

The McKinsey study also shows companies may be paying a penalty for lack of diversity. Companies in the bottom quartile in terms of gender and ethnic diversity are 29% more likely to underperform the national average in profitability when compared to the other three quartiles.[20]

(b) Lack of Diversity May Be Costing the Legal Industry Revenue

How does the legal profession stack up against these studies? As of 2017, the U.S. legal profession still struggles to match the broader population that it serves.[21] It lags behind many other professions in terms of gender, racial, and ethnic diversity.[22] The demographics are especially concerning for leadership positions in the legal profession. While minority lawyers now make up 16% of law firms (a record high), only 9% percent of law partners are people of color.[23] In the corporate sector, only 11% of general counsels at Fortune 500 companies are minorities.[24] To give these figures some perspective, minorities make up 40% of the U.S. population[25] and represent a third of the legal profession as a whole.[26] While the legal profession’s efforts to increase diversity have led to a more diverse pool of lawyers to choose from, these efforts are clearly not reaching the top.

These numbers take the legal profession out of the running under either study for high levels of diversity. On a positive note, these studies suggest that the potential for increased revenue is there for any legal business that resolves to increase diversity in its leadership and continue the effort to increase diversity in its general legal workforce. In our current state, however, the legal industry is casting aside untapped revenue and may even be paying a penalty for its lack of diversity.

(c) Potential Mechanisms of Diversity Causing Increased Revenue

There are a couple important mechanisms for how increased diversity may drive sales. From an internal standpoint, increased diversity may improve company decision-making. From an external standpoint, it may improve the businesses’ orientation in the market. Either one of these factors, or a combination of the two, may explain diversity’s positive effects on company sales. Both mechanisms stress the benefits of infusing multiple viewpoints into business operations.

Before discussing these potential causes, it is important to note when reviewing the results of these studies that a correlation does not mean causation. Simply because these studies found a parallel does not mean that one factor influenced the other. Without further research, it is still possible that diversity and sales figures are unrelated, or alternatively, increased sales figures influence companies to invest in diversity rather than the other way around. These correlative studies are mindful of their limitations, and those who hope to successfully apply these methods to the real world should be similarly cautious.[27]

Increased diversity may improve sales figures through improved company decision‑making. When faced with a company decision, a diverse set of employees are more likely to offer more diverse perspectives. Such contributions lead to more informed decision‑making. The Herring and McKinsey studies suggest that this explanation may be applicable regardless of the type of diversity (whether gender, racial, or ethnic). This explanation may also be applicable to the small, everyday decisions of the general workforce that add up. Having more diverse perspectives at the executive‑level or board‑level may have significant impact on decisions related to the general direction of a business that translate to better sales.

Increased diversity may also improve revenue by improving a company’s orientation to the market. A company that mirrors its market is better equipped to understand market dimensions and develop products and services that most of the population, and not just a small sector, want to buy. As the McKinsey study suggests, matching the market is likely not just important at the general workforce level, but also at executive and board levels.

Additionally, matching the market may attract increased investment. More so than their Baby boomer and Gen‑X counterparts, studies show that Millennials want to patronize socially conscious companies that not only pursue profit but also aim to better society.[28] One way that companies can display a commitment to social consciousness is through a diverse workforce and through diverse corporate representation.

While the number of corporations committed to diversity and giving business to diverse partners has increased, it is interesting to quantify the amount of revenue this has generated for diverse partners. According to a study by the Institute for Inclusion in the Legal Profession, it was found that few diverse partners were generating annual revenues of $1 million or more for these clients, with a substantial majority generating less than $500,000 annually.[29]

(d) Understanding the Link Between Diversity and Sales Still Has a Ways to Go

There is still work to be done to fully understand the relationship between diversity and sales performance. As noted above, correlation does not equal causation. It is unclear from present studies the direction in which causation runs.[30] The Herring and McKinsey studies do not foreclose the possibility that financial success may lead to increased investment in diversity, rather than the other way around.[31] The Herring study data came from 506 for‑profit business organizations from a 1996 to 1997 National Organizations Survey.[32] McKinsey assessed 1,007 companies across twelve countries by reviewing publicly available data on corporate websites, annual reports, and other industry websites between 2016–2017.[33] While these data cover a huge breadth of organizations—which is impactful in reaching statistically significant results—this type of data only uncovers part of the story. Causal insight will require a deeper dive into each business, i.e., a much more significant investment and more time‑consuming study.

There are many skeptics who claim that diversity is inconsequential or even harmful to business performance due to the introduction of conflict from differences.[34] While there are no empirical studies with hard numbers to back these claims against the case for diversity, the above contradictory research is still too nascent and incomplete to fully eviscerate these theories.

Finally, as the diversity of the U.S. population continues to evolve, updated figures in the Herring studies are needed. Although the gender composition of the United States is roughly the same, Professor Herring’s data is derived from a 1996–1997 time period when 75% of the U.S. population was white.[35] This number has since scaled back to 60%, which may have an impact on the sales figures.[36] Additionally, our definition of diversity is constantly expanding and evolving.[37] There is a need for a updated research on the issue of whether other types of diversity, such as cognitive diversity, life experiences, age, sexual orientation, religion, disability, and socioeconomic status, have the same association with sales as gender and ethnic diversity.[38]

(e) Conclusion—Diversity Is Associated with Increased Revenues

All criticisms and antithetical hypotheses considered, hard evidence supports the business case for workplace diversity. Herring’s study shows that there is value in promoting overall gender and racial diversity in the workforce while the McKinsey study shows that diversity at the top matters. More diversity is associated with increased profitability. Our legal industry should take note that a lack of company diversity may be hurting the bottom line.

II. Impact of Workforce Diversity on Market Share

(a) Studies Show Increased Diversity Is Correlated to Increased Market Share

As with increased sales and revenue, statistics show that companies prioritizing diversity have greater market share, greater ability to capture new shares of the market, and greater ability to retain current market share than companies with less diversity. It is not surprising that companies with diversity that reflects their customer base do a better job of capturing that customer base.

Accordingly, a study by the non-profit think tank Center for Talent Innovation in New York City showed that companies with diverse teams are 70% more likely to report the capture of a new market within the past year.[39] Those same companies were more than 45% more likely to report market growth in the prior year.[40] Diversity for purposes of that study was defined as two-dimensional (2D) diversity, in which leaders exhibited at least three kinds of both inherent diversity and acquired diversity.[41] Inherent diversity includes gender, race, age, religious background, socioeconomic background, sexual orientation, disability, and nationality.[42] Acquired diversity includes cultural fluency, generational savvy, gender smarts, social media skills, cross-functional knowledge, global mindset, military experience, and language skills.[43] In addition to increased market share, other benefits flowing from leadership with 2D diversity include employees who report that their ideas win endorsement from decision-makers (63% vs. 45% for companies without 2D diversity in leadership), get developed (48% vs. 30%), and get introduced to the market (35% vs. 20%).[44] Employees also report that leaders with acquired diversity are more likely to ensure that employees are heard (63% vs. 29% for employees whose leader has no acquired diversity traits), make employees feel safe introducing ideas (74% vs. 34%), empower teams to make decisions (82% vs. 40%), implement feedback (64% vs. 25%), give actionable feedback (73% vs. 30%), and share credit (64% vs. 27%).[45] Thus, leaders who are inherently diverse and have acquired diversity foster environments that are more conducive to new ideas and to marketing new ideas.

That environment of fostering new ideas is likely a leading driver of the increased market share experienced by diverse companies. The economic markets of the United States are becoming increasingly diverse, and by 2050 there will be no racial or ethnic majority.[46] New immigrants and their children will account for 83% of the growth in the working-age population between 2000 and 2050.[47] With an increasingly diverse population, companies that reflect the diversity of the population are more likely to experience market growth.[48] For example, as individuals responsible for selecting legal counsel diversify, those individuals are more likely to consider legal representation that reflects their diversity and to inquire about a law firm’s diversity in the selection process.[49] Thus, “diversity is probably a competitive differentiator that shifts market share toward more diverse companies over time.”[50] More diverse companies can more effectively market to more diverse consumers.[51] Another example of this is the philosophy of consumer goods company L’Oreal, which creates teams of multicultural employees for new product development and innovation.[52] “Their background is a kind of master class in holding more than one idea at the same time. They think as if they were French, American, or Chinese, and all of these together at once.”[53] Thus, L’Oreal is able to launch culturally relevant products and capture emerging markets.[54]

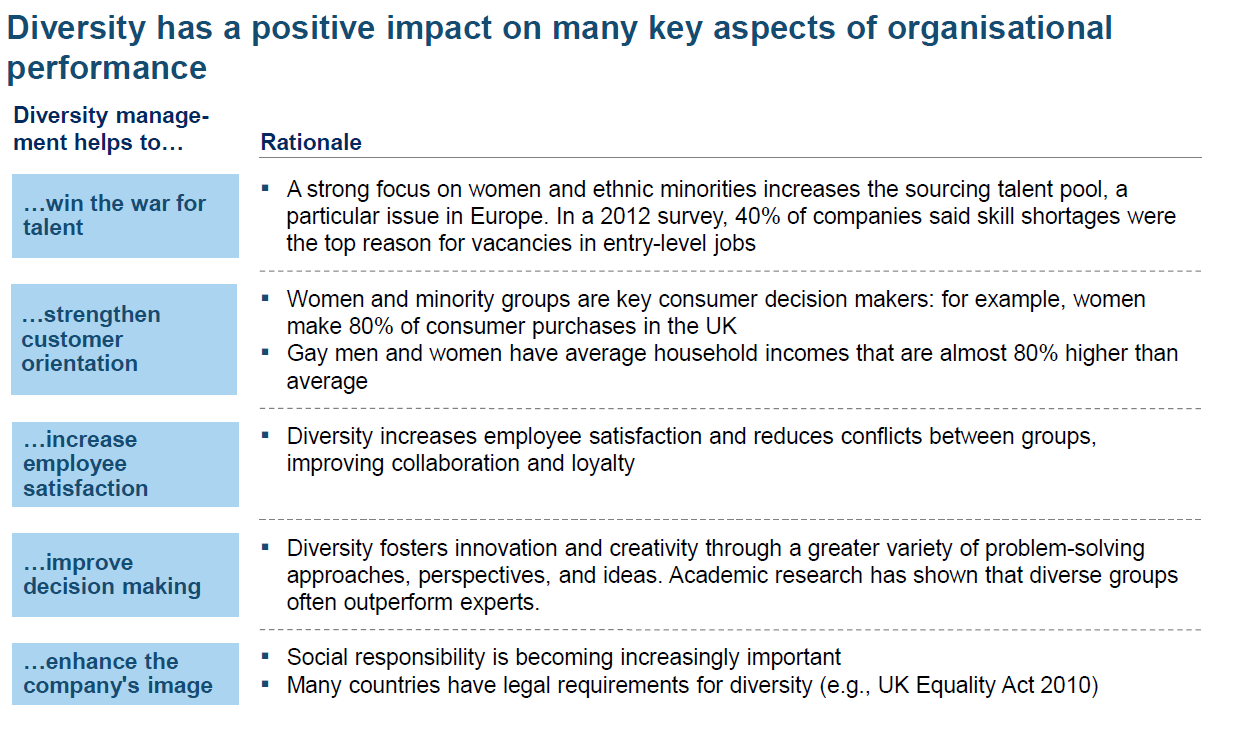

Diversity increases market share by increasing performance. Thus, a key study by McKinsey & Company noted the follow positive impacts on organizational performance:

Figure 1: Impact of Diversity on Key Aspects of Organizational Performance[55]

(b) Market Share in the Legal Profession

What is true for companies eventually becomes true for the legal profession. As companies see the increasing value of diversity in their businesses, they become more insistent on diversity in their legal teams. For example, Facebook requires that at least 33% of the lawyers in law firm teams working on their matters are women or ethnic minorities.[56] Law firms must also “actively identify and create clear and measurable leadership opportunities for women and minorities,” including acting as trial counsel.[57] HP, Inc. requires outside counsel to have at least one diverse relationship partner or to have at least one “woman and one racially/ethnically diverse attorney each performing at least 10 percent of the billable hours worked on HP matters.”[58] Noncompliance results in a 10% holdback of fees.[59] MetLife has a program to ensure firms provide sponsorship, coaching, and mentoring to diverse junior attorneys.[60] At the inception of its legal diversity initiative, Walmart shifted approximately $60 million worth of legal work to women or minority attorneys at its top 100 law firms.[61] Thus, as with corporations, firms looking to increase their market share with increasingly diverse clients would be well-served to increase the diversity of their teams.

In addition to increasing market share, statistics show that increasing diversity helps maintain current market share through client retention. One study found that gender-balanced entities, or entities having a gender balance of 40% to 60% women, had an average client retention rate that was nine percentage points higher than other entities.[62] The study by Center for Talent Innovation showed that a team with a member sharing a client’s ethnicity is 152% more likely than another team to understand that client.[63] A lawyer who is better able to understanding their client, including being sensitive to a client’s cultural taboos, expectations, and conflict-resolution styles will be more effective in establishing a relationship of trust and confidence with diverse clients and will implement more effective legal strategies.[64] Accordingly, firms are able to both maintain and expand their market share as a result of diversity efforts.

(b) Conclusion—Diversity Is Associated with Increased Market Share

As with increased revenues, studies show that workplace diversity is associated with increased market share. The study by the Center for Talent Innovation shows that diversity leads to market growth. In the legal industry, corporations and clients are insisting that their legal counsel be diverse. Further, diversity is associated with client and market retention.

II. Reduced Turnover Cost

(a) Turnover in General and Consequences

Turnover includes both voluntary and involuntary departures of employees at companies and is a cost to companies.[65] One study estimates the total cost of voluntary turnover in the U.S. in 2016 at $536 billion.[66] This figure is based on nearly thirty-eight million voluntary separations, costing a company an average of $15,000 per employee.[67] At time of the study, the average U.S. salary was $45,000; therefore, the average voluntary turnover cost equates to 33% of the average employee’s salary.[68] Another study found the cost of turnover to be 21% of the employee salary,[69] while other places the turnover cost as high as 93% of the departing employee’s annual salary.[70]

Many types of direct and indirect costs are associated with turnover costs for companies. Table 2 below shows common costs associated with turnover:

Table 2: Common Costs Associated with Turnover[71]

|

Direct costs |

Separation costs:

|

Replacement costs:

|

Training costs:

|

|

Indirect Costs |

Lost productivity:

|

||

(b) Diversity Turnover: Rates, Cost, and Causes

The turnover rate for African-Americans and women in the U.S. workforce is generally higher than the rate for white males.[72] For example, one study found a 40% higher turnover rate for African-Americans than for white employees, while several studies reported turnover for women to be twice as high as the rate attributed to men.[73] Additionally, women’s reported higher turnover rate was also found to be at all ages, not just during childbearing years.[74] For example, a large oil company in the late 1980s determined that its high potential women were leaving its company at two and a half times the rate of comparable men.[75]

The overall resulting cost due to high turnover among women and African-Americans is, therefore, likely significant for many companies.[76] Diversity turnover may impact a company’s business in terms of customer service and product development due to the company’s workforce no longer reflecting a diverse customer base, or the turnover of diverse employees may result in decreased innovation.[77] Also, the added recruiting, staffing, and training costs have been estimated to range between $5,000 to $10,000 per hourly employee and between $75,000 to $211,000 for an executive.[78] Finally, these high turnover rates by diverse employees may result in a revolving-door situation where employees are constantly learning or in training and never performing at full potential.[79] For example, a Fortune 500 utility company with twenty-seven thousand employees calculated a $15.3 million per year loss resulting from the costs associated with systematic gender bias, such as turnover and loss of productivity.[80]

Although the causes of turnover vary widely among employees, common cited reasons include the following: (1) better career opportunities; (2) work environment; (3) management behavior; (4) job characteristics; (5) compensation and benefits; and (6) work life.[81] For women, the lack of opportunity for career growth is the primary reason that professional and managerial women leave their jobs.[82] According to one survey, women were found to have higher turnover rates at all ages and not just during childbearing years.[83] This is true of millennial women who often do not cite motherhood as a reason for leaving their job.[84] One reason diverse groups may suffer from high turnover is stereotypes and favoritism, which often divide people into in-groups and out-groups.[85] Additionally, lack of workplace flexibility is an important factor impacting female turnover.[86] The report claims that 40% of women who do not have flexibility or a family-friendly manager plan to leave their job within a year.[87]

Accordingly, it seems to logically follow that a diverse workplace would lead to reduced turnover and reduced costs associated with turnover. The following is a case study from the 1980s of a company’s response to these issues.

Early in the 1980s, Corning realized that women and [African-Americans] were resigning from the company at more than twice the rate of white men, costing the company $2 to $4 million a year to recruit, train, and relocate replacements. Two quality teams were set up in 1987 to identify and address the issues facing women and [African-American] employees. They found that the barriers or challenges facing white males were not the same as those facing women and [African-Americans]. Corning embarked on a systemic intervention to change things. Then CEO Jamie Houghton was appalled that people in the corporation did not feel valued and felt they were not able to contribute. The intervention included mentoring, career development opportunities, a more progressive approach to child care and other work life balance programs, and training. Targets were set to raise the critical mass in the organization. An examination of performance and reward systems was conducted to ensure they were free of bias. The business case for this systemic intervention rested on the cost of replacement, the shrinking talent pool, and changing market demographics. Using a conservative estimate of $50,000 as the cost of turnover for an average employee, Corning estimated a savings of $5 million by reducing the attrition rate by 100 people. Corning’s goal was to have an employee population that mirrored the face of the country. Given the demand for diverse talent, it maintained that a company that was not diversity-friendly would have a difficult time attracting and retaining such talent.

Finally, the company saw the changes taking place in marketplace. As the population it was selling to changed, the marketing and sales strategies had to be shaped by a workforce that thought, acted like, and understood the marketplace.

After five years the company has realized the necessary critical mass. Thirty five percent of the management workforce was female, up from almost none in the early 1980s. A relatively recent climate survey showed that the views of the corporation by men and women employees are virtually the same on 40 key questions having to do with career development, fairness, and employee value, among other things.[88]

Another report attempts to calculate the cost savings from diversity turnover from a hypothetical ten thousand employee organization.[89] In this hypothetical, 35% of personnel are either women or African-Americans, and the white male turnover rate is 10%.[90] Using the differential turnover rates for women and African-Americans of roughly double the rate for white males discussed above, a loss of 350 additional employees is estimated from the women and African-American groups.[91] If half of the turnover rate difference can be eliminated with better management and the total turnover cost average is $20,000 per employee, then the resulting potential annual cost savings would be $3.5 million.[92] Such cost savings figures are rarely advertised by companies, however, in the case of one pharmaceutical company, Ortho Pharmaceuticals, a total savings of $500,000 from reduced diversity turnover has been reported.[93]

(c) Conclusion

In response to the costs associated with diversity turnover, it has been suggested that inclusive leaders that value their employees’ unique diversity may form higher quality relationships based on shared power, mutual trust, and respect, and thus help reduce the diversity turnover.[94]

V. Mitigating Legal Costs

(a) Legal Costs of Discrimination Actions

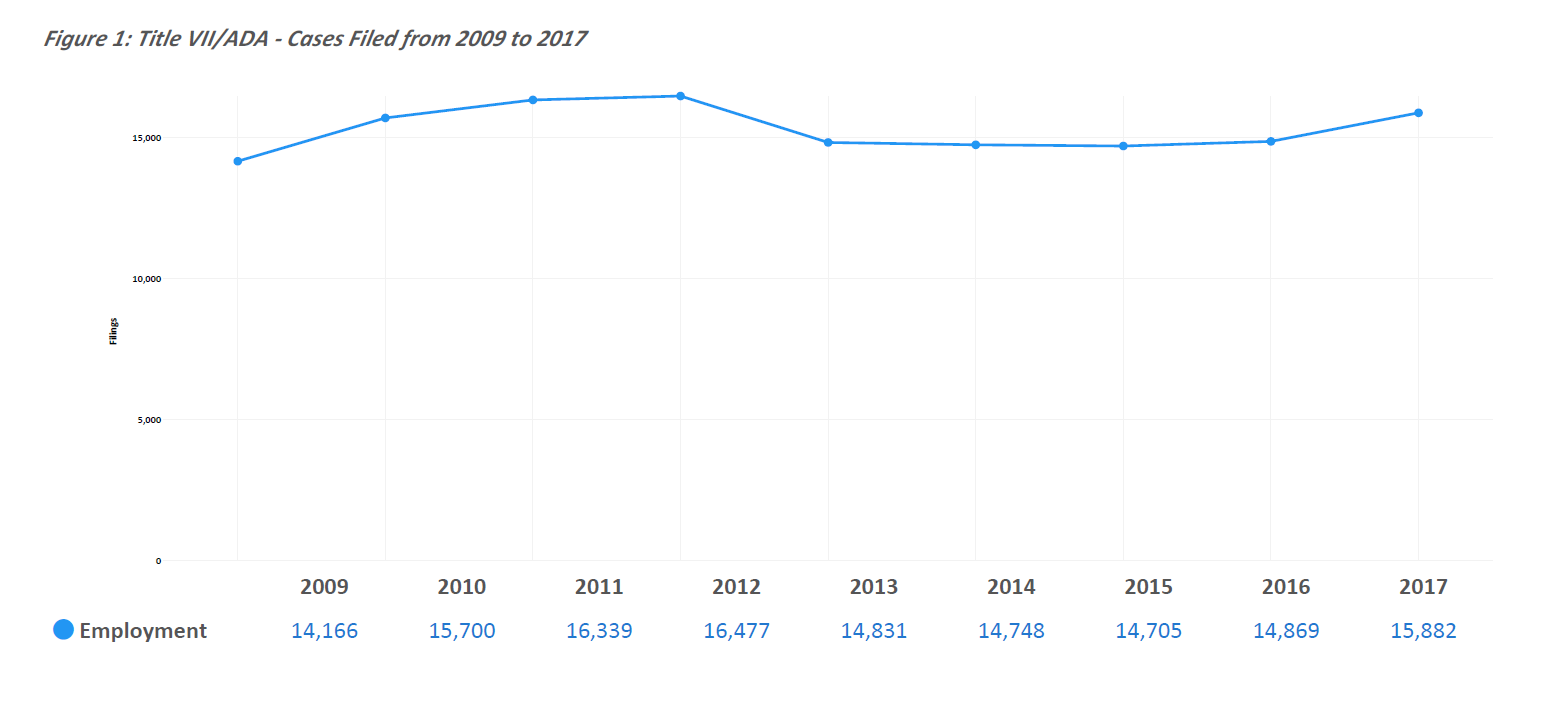

Companies with strong diversity policies stand to benefit in the litigation context by avoiding and/or mitigating both indirect and direct litigation costs associated with discriminatory-based legal complaints, i.e., discrimination based on race and color,[95] sex, national origin, and religion. This is particularly important as discrimination lawsuits are one of the most common type of legal action filed by employees. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) reports that the highest number of employment discrimination charges in its 45-year history were filed in the fiscal year ending on September 30, 2010. Similarly, Lex Machina, a data analytics company that tracks trends in the legal industry, also reports that filings for Title VII/ADA cases peaked in 2010/2011, remained relatively consistent from year-to-year, and increased in 2017:[96]

Figure 2: VII/ADA—Cases Filed from 2009 to 2017[97]

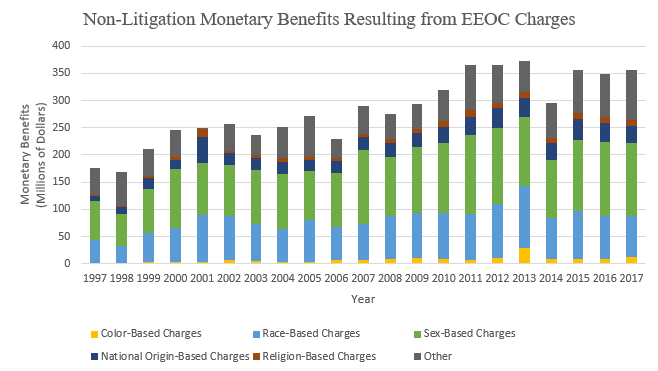

Defense costs related to employment discrimination litigation are high. The EEOC publishes statistics on monetary benefits for discriminatory-based complaints. Out-of-court EEOC resolutions alone, from 1997 through 2017,[98] have a price tag of $355.6 million, which shows an upward trend relative to the years prior. These values do not include litigation resolutions or charges stemming from complaints filed with state or local Fair Employment Practices Agencies:

Figure 3: Non-Litigation Monetary Benefits Resulting from EEOC Charges

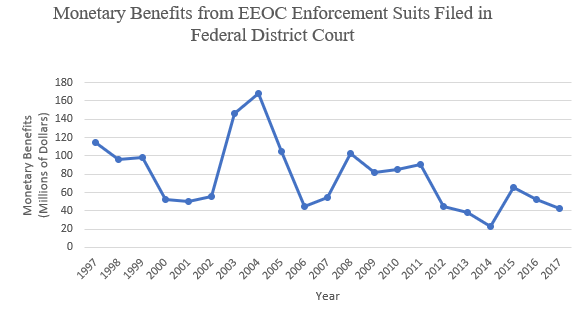

Likewise, the EEOC has published reports of monetary payouts for discrimination in federal district court litigation[99] in the last ten years. These values range from $22.5 million (2014) up to $168.6 million (2004):

Figure 4: Monetary Benefits from EEOC Suits Filed in Federal District Court

While these numbers represent tangible costs associated with discriminatory practices, they only tell half the story. The damage to reputation and the costs of resources during litigation, such as employees’ time away from their primary job and marketing efforts to try to re-build the company’s reputation are among the intangible costs of discriminatory practices. Reputation has long been recognized as a valuable intangible asset to an organization,[100] allowing it to: charge premium prices, attract top talent, gain or improve access to capital markets, and incentivize investors.[101]

Further, costs associated with discrimination do not always arise from formal complaints. For instance, in April of 2018, Starbucks Corporation publicly apologized for an incident at one of its Philadelphia stores. Police were called and they arrested two African-American men for suspicion of trespassing, which the Philadelphia mayor described as exemplifying “what racial discrimination looks like in 2018.”[102] In response, Starbucks announced that it would close all of its stores for an afternoon to train 175,000 employees in racial-bias education.[103] One estimate suggests that the half-day closure cost the company $16.7 million in lost sales.[104] Additionally, Starbucks reached an agreement with the individuals that included a confidential financial settlement.[105] Starbucks’s response suggests that it understands the public reaction and the need for its correction—even at a significant price point.

(b) Anti-Discrimination Policies and Procedures Can Mitigate the Legal Costs of Discrimination

In the age of growing diversity and strides towards inclusion, corporations can stand to benefit from prudent anti-discriminatory policies and practices that help distance them from potentially harmful legal disputes that oftentimes leave them with long-lasting and unfavorable public perceptions. A diversity and inclusion program helps shield an organization from legal liability.

For example, diversity and inclusion programs can signal to courts that an organization complies with anti-discrimination laws.[106] The Supreme Court partially relied on the existence of Wal-Mart’s anti-discrimination policy to conclude that there was no significant proof that Wal-Mart operated under a general policy of discrimination in a class action case.[107] However, some argue that the impact of anti-discrimination laws may be weakened when judges view organizational structures as indicators of legal compliance even in the face of discriminatory actions.[108] Thus, organizations are wise to take measures, in their diversity and inclusion programs, to go beyond shielding their organization from legal and procedural claims and to protect the interests of underrepresented groups.[109]

A company’s reputation can also affect the outcome of discrimination lawsuits, but with limitations. A recent study by the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University researched the effects of a company’s reputation and prestige on the outcome of discrimination lawsuits.[110] This study involved an analysis of more than 500 employment discrimination lawsuits between the years 1998 and 2008. The researchers found that the greater the company’s prestige, the less likely it would be found liable of discrimination. They termed this result as the “halo effect.” Interestingly, the study also found that once a prestigious company was found liable, punishment (in terms of damages) was much more severe. Prestige therefore is both a benefit and a liability, i.e., a “halo tax,” in employment discrimination lawsuits.

(c) Conclusion

A company’s anti-discriminatory policies, procedures, and practices can help avoid or reduce employment discrimination lawsuits. Organizations are therefore wise to implement strict policies against employment discriminatory practices in addition to working to instill an anti-discriminatory culture.

VI. ROI on Diversity Initiatives

(a) Spending on Diversity Initiatives

In view of the increased media and social focus on diversity of organizations, as well as the benefits of a diverse workforce, companies are spending more than ever on diversity initiatives. In 2015, Intel established a $300 million fund to be used by 2020 (about $60 million per year) to improve the diversity of the company’s workforce.[111] In the same year, Google unveiled a $150 million plan to implement several diversity initiatives, such as encouraging women and minorities to enter the tech industry,[112] and Apple committed over $50 million on diversity initiatives, including donations and partnerships with historically black colleges and universities, and the National Center for Women in Information Technology.[113]

According to one estimate, Fortune 500 companies invest, on average $32 million annually on hiring, with about $2.5 million of that budget dedicated to recruiting minority candidates.[114] By another estimate, companies spend, in total, about $8 billion per year in diversity training and spending.[115]

While research shows that having diversity provides positive economic benefits, the dollar return on investment (ROI) of specific diversity initiatives is difficult to calculate. Diversity and inclusion practices, such as hiring and promoting from a more diverse pool of candidates, can take years to see an effect. Additionally, the benefits associated with diversity initiatives are often softer, intangible results, like improved employee engagement, teamwork, and communication.[116]

It is little surprise then that if senior leaders find it difficult to believe that they will attain a positive ROI of dollars spent on diversity and inclusion programs, they will hesitate to invest in diversity initiatives.

(b) Types of Diversity Efforts

To further complicate the issue, studies have shown that standard diversity training programs do little to increase certain measurable demographic diversity indicators.[117] For example, mandatory diversity training is often remedial rather than proactive in nature, uses negative messaging, and hence incites anger and backlash.[118] Additionally, particularly in the case of one-time training sessions, participants display positive results and outlooks immediately after the session, but long-term behaviors and beliefs are not as easily changed.[119]

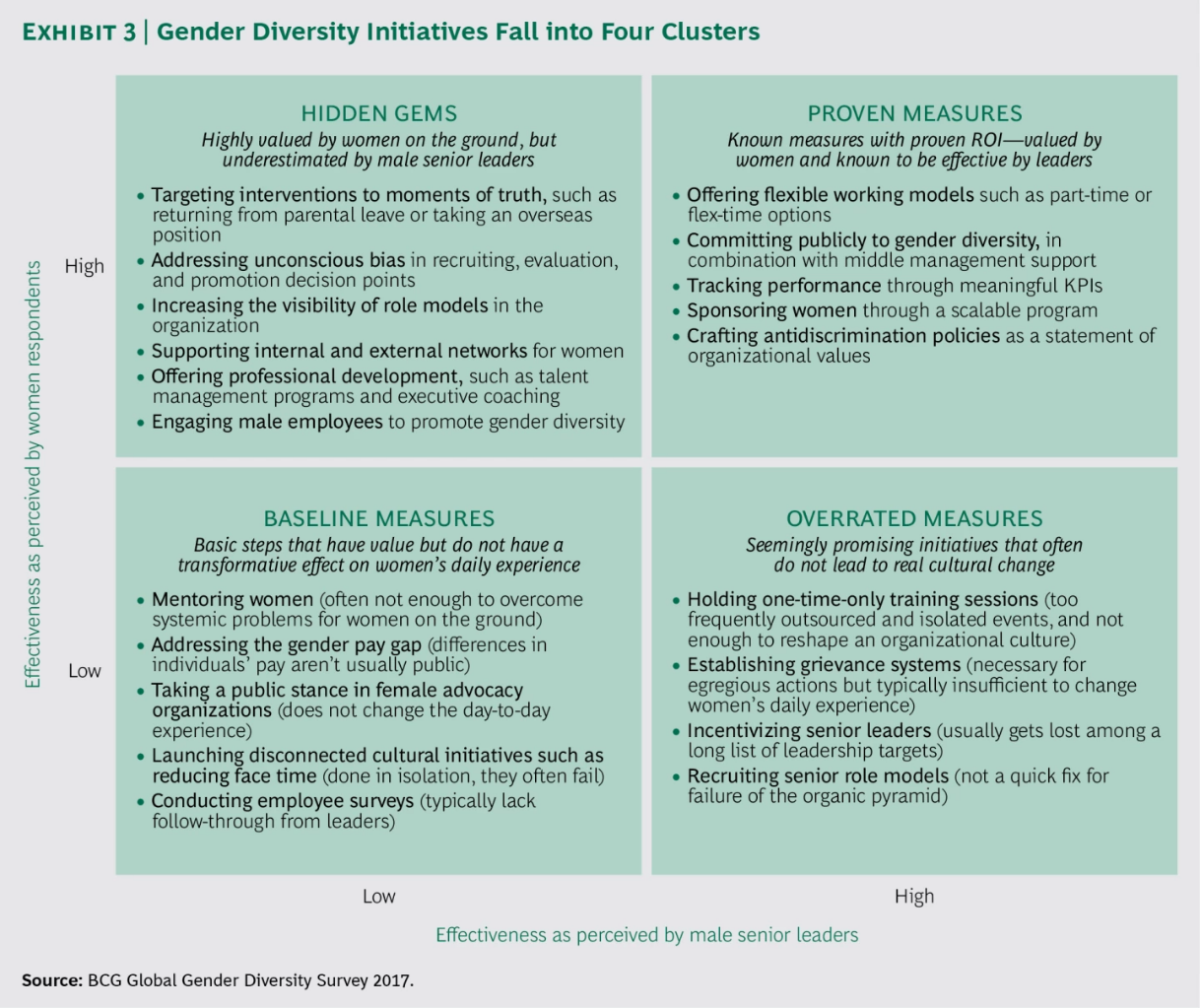

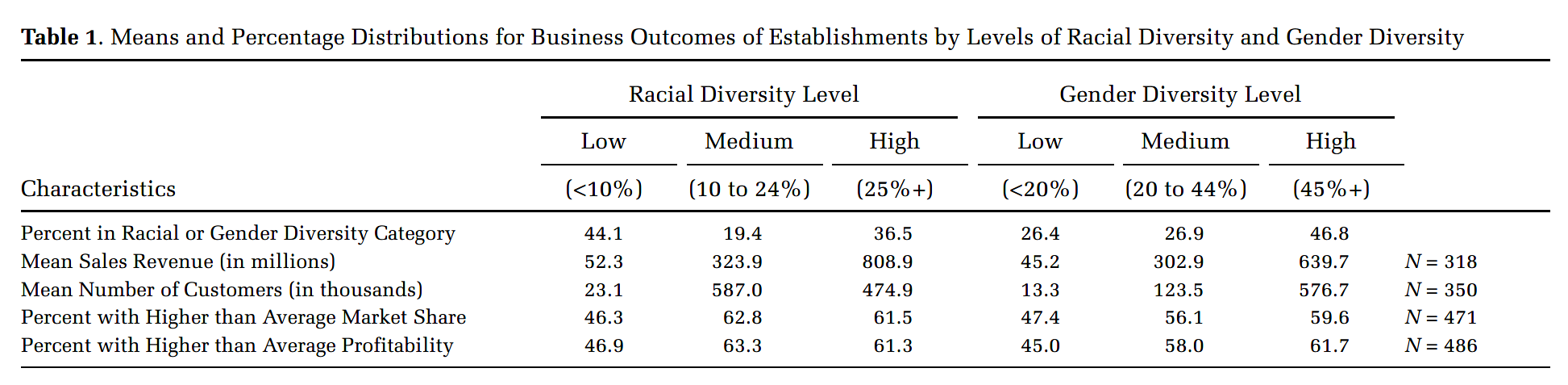

On the other hand, programs like voluntary training, mentoring, diversity task forces, and diversity managers are proven to do a better job increasing demographic diversity.[120] For example, Table 3 shows that programs such as these have resulted in increases of between 3% and 10%, and in some cases more in the proportion of women and minorities in managerial positions in U.S. companies.[121]

Table 3: Percent Change Over Five Years in Representation Among Managers[122]

Diversity programs like mentoring, recruiting, and self-managed teams typically are not explicitly marketed as being “diversity” initiatives and encourage managers and leaders to be more positively engaged with individuals, rather than critiquing hiring and managerial styles. Additionally, active company policies such as flexible working hours and paid parental leave reinforce the company’s support of the diverse needs of employees.[2] These programs also have a markedly higher ROI, both as perceived by women and in dollar value. For example, Figure 6 shows the effectiveness of diversity initiatives as perceived by women, as compared to their effectiveness as perceived by male leaders.

Figure 5: Perceived effectiveness of diversity initiatives [124]

Note that “mentoring” in Figure 6 refers to an informal relationship with a senior leader, while “sponsorship” refers to formal structure, including lobbying for them to receive promotions, training, and key assignments. “Mentoring” in Table 3 is more closely tied to “sponsorship,” in which mentor-mentee partners are supported via a formal mentorship program, and mentors sponsor their mentees for key training and assignments.

As can be seen, measures that support positive engagement, like offering flexible working models, sponsoring women (and minorities), and engaging male employees tend to be more effective than one-time training sessions and grievance systems. It is important for leaders to realize that for diversity and inclusion programs to be a success, they need to be approached strategically to maximize the efficacy, and hence, the ROI, of the program.

(c) Calculation of ROI

Supporters of diversity initiatives often feel the need to make the business case for promoting diversity in the workplace. [125] Accordingly, the ROI often becomes a pivotal factor in gaining the support of others in diversity initiatives. [126] Numerous metrics may be used to determine ROI, which are often specific to a company’s mission statements, goals, and financial and other targets, among other factors. Many organizations consider employee retention and satisfaction, increased penetration of market share, lawsuit prevention, and external recognition of their diversity initiatives when determining ROI of such initiatives. [127] Despite studies that have concluded “that ethnic and cultural diversity on executive teams continues to correlate strongly with financial performance to support the argument that promoting ethnic and cultural diversity in companies is extremely valuable,” [128] the number of empirical studies for ROI on diversity initiatives appear to be relatively limited for numerous reasons. [129] Nevertheless, the remainder of this section summarizes several relevant case studies.

(d) Case Study #1: National Organizations Survey

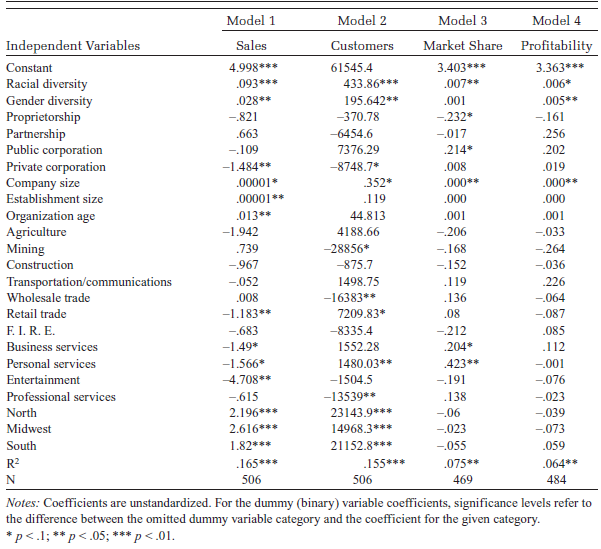

Data from a 1996 to 1997 National Organizations Survey from 506 for-profit business organizations was analyzed by Professor Cedric Herring of the University of Illinois. [130] Dr. Herring concluded that the data showed “a positive relationship” between racial and gender diversity and overall business function. [131] Dr. Herring performed multivariate analyses using various models to account for limitations in the survey data. [132]

Table 4: Regression Equations Predicting Sales, Number of Customers, Market Share, and Relative Profitability with Racial and Gender Diversity and Other Characteristics of Establishments

Models 1-4 summarize that racial diversity is statistically significant in each of the given models, while gender diversity was statistically significant in Models 1, 2, and 4. [133] In Models 1, 2, and 4, racial and gender diversity “were not only related to sales revenue, but were some of the most important predictors of increased sales revenues.” [134] In Model 3, racial diversity “maintained a significant relationship to the market share” among other factors. [135] Overall, the multivariate analyses suggest that diversity is generally associated with “increased sales revenue, more customers, greater market share, and greater relative profits,” and, thus, the business case for diversity initiatives certainly exists. [136]

(e) Case Study #2: Mentoring at Sodexo

The following is a summary of a case study of the ROI of a formal mentorship program at Sodexo, Inc.:

Sodexo, Inc. launched its North American mentoring initiative in 2005 based on strong empirical evidence regarding the importance—for both employee development and business success—of corporate mentoring programs and linking mentoring to positive Return on Investment (ROI). Sodexo’s initiative, Spirit of Mentoring, comprises three mentoring opportunities that aim to cultivate a diverse, inclusive culture; increase overall strength and diversity of the leadership pipeline; improve employee retention; and foster connections for employees dispersed across the continent.

Sodexo’s formal mentoring program, called IMPACT, is tied to ROI results. It is a structured, yearlong initiative designed for mid-level managers and above, including the C-suite level who serve as mentors. Mentors are typically at least two job grades above mentees. A cross-functional implementation team that is chaired by the Director of Diversity & Inclusion Initiatives administers the program, and two executive sponsors at the President level are leveraged to sustain the initiative over time.

As part of its commitment to diversity, Sodexo strives for cross-cultural and cross-gender mentoring partnerships. In 2008, 70 percent of pairs were composed of individuals from different cultures or of different genders, exceeding Sodexo’s goal of 60 percent. In addition, 90 percent of pairs were employees from different operational and administrative business areas. Finally, approximately 40 percent to 50 percent of participants were women, reflecting Sodexo’s employee composition. Research demonstrating that corporate mentoring is linked to positive ROI is the business case IMPACT is based on. Sodexo examines ROI directly related to mentoring activities three to six months following the conclusion of an IMPACT cycle, when it gathers qualitative and quantitative feedback from both mentees and mentors. This process aligns the mentoring programs with other internal diversity, inclusion, and business strategies and determines exactly how IMPACT has affected company D&I initiatives and the business itself.

To assess ROI, Sodexo examines the ratio of the cost to run IMPACT to the financial gains made by IMPACT participants, particularly mentees. Participants are asked to estimate: how the program affected and continues to affect their day-to-day work; the business accomplishments that they are able to attribute to contacts made during their participation in IMPACT; and their confidence levels related to these estimates.

In 2009, the program received a ROI of 2 to 1, which is largely attributable to enhanced productivity and employee retention. [137]

In short, by obtaining qualitative and quantitative feedback about outcomes related to the mentorship program, Sodexo was able to attribute an ROI of $2 saved and/or earned for every dollar spent on implementing the mentorship program. Notably, the ROI Sodexo’s IMPACT program is evaluated only for three to six months after the formal mentorship period ends. However, the skills, relationships, and enhanced employee productivity and happiness may continue to affect work, accomplishments, and ultimately, economic benefits beyond this period.

(f) Case Study #3: Flexible Working Models for Caregivers

A 2016 collaborative study between AARP (American Association of Retired Persons) and ReACT (Respect a Caregivers’ Time) examined the business case for family caregiver policies, including implementing flextime and telecommuting options for caregivers to balance jobs with caretaking responsibilities. [138]

The study considered the benefits and costs of family-friendly policies including reduced human capital costs for recruitment and turnover, increased productivity, reduced absenteeism, increased performance at work, costs of payouts, costs of benefit set-up and costs benefit administration. [139]

The study concluded:

We estimate a midpoint ROI for offering flexible work hours between 1.70 (assuming average annual salary of $50,000) and 4.34 (assuming average annual salary of $100,000). About half of the ROI is explained by lower absenteeism, about 30 percent by increased employee retention and about 20 percent by better recruitment.

Midpoint ROI for offering a telecommuting option on a part-time basis is estimated between 2.46 (assuming average annual salary of $50,000) and 4.45 (assuming average annual salary of $100,000). As there was limited information on the specific effect size of retention, recruitment and absenteeism, the estimates rely on global ratings of productivity by employees and employers. [140]

(g) Conclusion

While empirical studies for ROI on diversity initiatives are limited, several case studies demonstrate that investing in diversity initiatives tends to result in a positive ROI, for example, by enhancing productivity and employee retention while reducing absenteeism. In particular, diversity initiatives such as mentoring and flexible work models can positively engage diverse employees and help maintain balance for each employee’s diverse needs. As a result, they are proven to be effective diversity initiatives, both perceptively and economically, with a ROI of about $2 for every $1 spent on mentoring and between $1.70 to $4.45 for every $1 spent on flexible working models.

VII. Conclusion

As discussed above, evidence supports the business case for diversity in the workplace. Firms and companies should invest in initiatives to hire and retain diverse employees, or risk hurting their bottom lines.

Read more: https://ipo.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/FINAL-White-Paper-on-Economics-of-Diversity-1.pdf

Citations

[1] Co-authors—Jennifer Carter (Baker Botts LLP), Shruti Costales (HP Inc.), Mareesa Frederick (Finnegan, Henderson, Farabow, Garrett & Dunner, LLP), Natalie Gonzales (Baker Botts LLP), Elisabeth Healey (Vorys, Sater, Seymour and Pease LLP), Maryam Imam (Klintworth & Rozenblat IP LLP), Christina Lee (Perry + Currier Inc.), Nila Ray (Fletcher Yoder), Rachael Rodman (Ulmer & Berne LLP), Sherri Wilson (Dykema Gossett PLLC), and Bailey Ziegler (TraskBritt, P.C.).

[2] Cedric Herring, Does Diversity Pay?: Race, Gender, and the Business Case for Diversity, 74 Am. Soc. Rev. 208 (2009).

[3] Herring, supra note 2, at 208.

[4] Herring, supra note 2, at 215.

[5] Cedric Herring, Is Diversity Still a Good Thing?, 82 Am. Soc. Rev. 868, 871 tbl.1 (2017).

[6] Herring, Is Diversity Still a Good Thing?, supra note 5, 871 tbl.1.

[7] Id.

[8] Herring, supra note 2, at 217.

[9] Herring, supra note 2, at 218.

[10] Vivian Hunt et al., Delivering Through Diversity, McKinsey&Company (Jan. 2018), https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/business%20functions/organization/our%20insights/delivering%20through%20diversity/delivering-through-diversity_full-report.ashx.

[11] Hunt, supra note 10, at 8.

[12] Hunt, supra note 10, at 8.

[13] See, e.g., Hunt, supra note 10, at 10.

[14] Hunt, supra note 10, at 8.

[15] Hunt, supra note 10, at 10.

[16] Id. Though there was also a correlation between gender diversity at the executive level and profitability, it was not statistically significant. Id.

[17] Hunt, supra note 10, at 12.

[18] Id.

[19] Hunt, supra note 10, at 13.

[20] Hunt, supra note 10, at 14.

[21] Elizabeth Chambliss, The Demographics of the Profession, IILP Review 2017: The State of Diversity and Inclusion in the Legal Profession 13 (2017), http://www.theiilp.com/mwg-internal/de5fs23hu73ds/progress?id=wU5HkVy6uLxavn5k4NSOHi4Bmw5c7_szq99NBZOQ3dA,&dl.

[22] Id.

[23] Tracy Jan, The Legal Profession is Diversifying. But Not at the Top., Wash. Post Wonkblog (Nov. 27, 2017), http://wapo.st/2hUFfVS?tid=ss_tw&utm_term=.bce490a1ba9e.

[24] Id.

[25] See QuickFacts United States, U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045217 (last visited Sept. 4, 2018) (displaying U.S. racial composition as of July 1, 2017).

[26] Jan, supra note 23.

[27] See Herring, supra note 2, at 216 n.3; Hunt, supra note 10, at 4, 38–39.

[28] AJ Agrawal, Millennials Want Transparency and Social Impact. What Are You Doing to Build a Millennial‑Friendly Brand?, Entrepreneur (May 31, 2018), http://entm.ag/hzm.

[29] http://www.theiilp.com/resources/Documents/IILPBusinessCaseforDiversity.pdf.

[30] Deborah L. Rhode, The Trouble with Lawyers 79 (2015).

[31] Rhode, supra note 30, at 79.

[32] Herring, supra note 2, at 213.

[33] Hunt, supra note 10, at 35.

[34] Herring, supra note 2, at 208.

[35] Herring, supra note 2, at 214.

[36] See QuickFacts United States, U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045217 (last visited Sept. 4, 2018) (displaying U.S. racial composition as of July 1, 2017).

[37] See generally Christie Smith et al., The Radical Transformation of Diversity and Inclusion: The Millennial Influence, Deloitte Univ. (2015), https://launchbox365.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/us-inclus-millennial-influence-120215.pdf.

[38] Id.

[39] Sylvia Ann Hewlett, et al., Executive Summary to Innovation, Diversity, and Market Growth (Center for Talent Innovation 2013), http://www.talentinnovation.org/assets/IDMG-ExecSummFINAL-CTI.pdf.

[40] See id.

[41] See id.

[42] See id.

[43] See id.

[44] See id.

[45] See id.

[46] Sophia Kerby & Crosby Burns, The Top 10 Economic Facts of Diversity in the Workplace, Center for American Progress (July 12, 2012), https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/news/2012/07/12/ 11900/the-top-10-economic-facts-of-diversity-in-the-workplace/.

[47] See id.

[48] See id.

[49] Shari Tivy, et al., The Association of Legal Administrators Diversity Toolkit, Institute for Inclusion in the Legal Profession Review 2017: The State of Diversity and Inclusion in the Legal Profession (2017), http://www.theiilp.com/resources/Pictures/IILP_2016_Final_LowRes.pdf.

[50] Vivian Hunt, et al., Why Diversity Matters, McKinsey & Company (Jan. 2015), https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/why-diversity-matters.

[51] Kerby et al., supra note 46.

[52] Christine Del Castillo, Diversity in the Workplace: The Case for Building Diverse Teams, Workable (June 2, 2016), https://resources.workable.com/blog/diversity-in-the-workplace.

[53] See id.

[54] See id.

[55] Hunt, supra note 50.

[56] Ellen Rosen, Facebook Pushes Outside Law Firms to Become More Diverse, The New York Times: DealBook (Apr. 2, 2017), https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/02/business/dealbook/facebook-pushes-outside-law-firms-to-become-more-diverse.html.

[57] See id.

[58] See id.

[59] See id.

[60] See id.

[61] Walmart Stores Inc., Wal-Mart Requires Diversity in its Law Firms (2005), https://corporate.walmart.com/_news_/news-archive/2005/12/09/wal-mart-requires-diversity-in-its-law-firms.

[62] Sodexo, Sodexo’s Gender Balance Study 2018 (2018), http://sodexoinsights.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/GenderBalanceStudy_2018_FINAL.pdf.

[63] Hewlett, supra note 39.

[64] Sylvia Stevens, Cultural Competency: Is There an Ethical Duty, Oregon State Bar Bulletin (Jan. 2009), https:// www.osbar.org/publications/bulletin/09jan/barcounsel.html.

[65] L. Sears, 2017 Retention Report: Trends, Reasons & Recommendations, Work Institute 9 (2017).

[66] Id.

[67] See id.

[68] See id.

[69] H. Boushey & S. J. Glynn, There Are Significant Business Costs to Replacing Employees, Center for American Progress (2012).

[70] G. Robinson & K. Dechant, Building a Business Case for Diversity, 11 The Acad. Management Executive 21, 23 (1997).

[71] L. Sears, supra note 65.

[72] T. H. Cox & S. Blake, Managing Cultural Diversity: Implications for Organizational Competitiveness, 5 Acad. Management Executive 45, 46 (1991).

[73] G. Robinson, supra note 70; see also T. H. Cox, supra note 71; J. Sullivan, Diversity’s Revolving Door — With 2x the Turnover, a Diversity Retention Program Is Needed, https://www.ere.net/diversitys-revolving-door-with-2x-the-turnover-a-diversity-retention-program-is-needed (2017).

[74] G. Robinson, supra note 70.

[75] Id.

[76] Id.

[77] J. Sullivan, supra note 72.

[78] G. Robinson, supra note 70. One study noted that women’s reasons to leave are most different for young employees and become almost equally similar for older employees. See L. Sears, supra note 65, at 21.

[79] G. Robinson, supra note 70.

[80] Id. (This high figure did not include sexual harassment costs).

[81] L. Sears, supra note 65; see also T. H. Cox, supra note 72.

[82] G. Robinson, supra note 70.

[83] T. H. Cox, supra note 72.

[84] L. Noel & C. H. Arscott, Millennial Women: What Executives Need to Know About Millennial Women, ICEDR (2015).

[85] L. H. Nishii & D. M. Mayer, Paving the Path to Performance: Inclusive Leadership Reduces Turnover in Diverse Work Groups, Cornell Center for Advanced Human Resource Studies Research Link (2010).

[86] Working Mothers, Mom’s @ Work 8 (2015).

[87] Id.

[88] G. Robinson, supra note 70 at 28.

[89] T. H. Cox, supra note 72 at 48.

[90] Id. at 46.

[91] Id.

[92] Id. (this example only addresses turnover, and additional savings may be realized from other changes such as higher productivity levels).

[93] T. H. Cox, supra note 72.

[94] L. H. Nishii, supra note 85.

[95] The EEOC defines race and color discrimination as follows: “Race discrimination involves treating someone (an applicant or employee) unfavorably because he/she is of a certain race or because of personal characteristics associated with race (such as hair texture, skin color, or certain facial features.) Color discrimination involves treating someone unfavorably because of skin color complexion.” See https://www.eeoc.gov/laws/types/race_color.cfm (accessed August 28, 2018).

[96] Lex Machina, Employment Litigation Report 2018, at p. 9.

[97] Id.

[98] https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/all.cfm (accessed August 28, 2018).

[99] https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/litigation.cfm (accessed August 28, 2018).

[100] See Damion Waymer & Sarah VanSlette, Corporate Reputation Management and Issues of Diversity, in The Handbook of Communication and Corporate Reputation 471–483 (Craig E. Carroll ed., 2013).

[101] Id. at 473.

[102] https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/15/us/starbucks-philadelphia-black-men-arrest.html (accessed August 29, 2018).

[103] https://www.businessinsider.com/starbucks-closures-arrest-cost-millions-2018-4 (accessed August 29, 2018).

[104] https://www.bloombergquint.com/business/2018/04/17/starbucks-training-shutdown-could-cost-them-just-16-7-million#gs.mHlHGZ0 (accessed August 29, 2018).

[105] https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/02/us/starbucks-arrest-philadelphia-settlement.html (accessed August 29, 2018).

[106] Lauren B. Edelman, et al., When Organizations Rule: Judicial Deference to Institutionalized Employment Structures, 117:3 Am. J. Econ. of Sociology 888 (2011).

[107] Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Dukes, 564 U.S. 338, 353–54 (2011) (“The second manner of bridging the gap requires ‘significant proof’ that Wal-Mart ‘operated under a general policy of discrimination.’ That is entirely absent here. Wal-Mart’s announced policy forbids sex discrimination, and as the District Court recognized the company imposes penalties for denials of equal employment opportunity.”) (citations omitted).

[108] Edelman, supra note 106, at 888 (2011).

[109] https://hbr.org/2016/01/diversity-policies-dont-help-women-or-minorities-and-they-make-white-men-feel-threatened (accessed September 7, 2018).

[110] Mary-Hunter McDonnell, et al., Order in the Court: The Influence of Firm Status and Reputation on the Outcomes of Employment Discrimination Suits, available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2373974 (2017).

[111] Wingfield, N, Intel Allocates $300 Million for Workplace Diversity, The New York Times (2015), https://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/07/technology/intel-budgets-300-million-for-diversity.html.

[112] Kelly, H, Google commits $150 million to diversity, CNN.com, (2015), https://money.cnn.com/2015/05/06/technology/google-diversity-plan/.

[113] Lev-Ram, M, Apple commits more than $50 million to diversity efforts, Fortune, (2015), http://fortune.com/2015/03/10/apple-50-million-diversity/.

[114] Stanley, O, Out of corporate America’s diversity failures, a new industry is emerging, Quartz at Work, (2017), https://qz.com/work/1092540/techs-diversity-failures-are-a-massive-business-opportunity-for-the-minority-recruitment-industry/.

[115] Lipman, J., How Diversity Training Infuriates Men and Fails Women, Time, (2018), http://time.com/5118035/diversity-training-infuriates-men-fails-women/.

[116] Diversity Best Practices, The ROI of Diversity and Inclusion, in D. B. Practices, Diversity Primer (2009).

[117] F. Dobbin, F. & A. Kalev, Why Diversity Programs Fail, Harvard Business Review (2016), https://hbr.org/2016/07/why-diversity-programs-fail.

[118] Id.

[119] Garcia-Alonso, J., Krentz, M., Brooks Taplet, F., Tracey, C., & Tsusaka, M., Getting the Most from Your Diversity Dollars, The Boston Consulting Group (2017), https://www.bcg.com/en-ca/publications/2017/people-organization-behavior-culture-getting-the-most-from-diversity-dollars.aspx.

[120] Dobbin, supra note 116.

[121] Id.

[122] Id.

[123] Lipman, supra note 114.

[124] Garcia-Alonso, supra note 118.

[125] Konrad, A. M., Prasad, P., & Pringle, J. K. (2006). The handbook of workplace diversity. London, Sage Publications.

[126] Id.

[127] Smiley, L. (2016, October 10). 5 Must-Have Metrics for Diversity & Inclusion to Prove ROI. Retrieved from: http://www.societyfordiversity.org/5-must-have-metrics-for-diversity-inclusion-to-prove-roi/

[128] Hunt, V., Yee, L., Prince, S., & Dixon-Fyle, S. (2018). Delivering through diversity https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/delivering-through-diversity

[129] Konrad, supra note 126.

[130] Herring, supra note 1, at 208-224.

[131] Id.

[132] Id.

[133] Id.

[134] Id.

[135] Id.

[136] Id.

[137] Catalyst, Making Mentoring Work (2010).

[138] AARP and ReACT, Determining the Return on Investment: Supportive Policies for Employee Caregivers (2016).

[139] Id.

[140] Id.

Share